David Vaughn – President of Integrated Resilience, LLC

Jeff Plumblee – Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Clemson University

Resilience is an area of growing concern due to climate change, population growth and migration, and a constantly growing dependency and interconnectivity of infrastructure. Over the years the need to comprehensively address all aspects along the resilience continuum has become ever more important. In conjunction with several co-authors, we have tried to address this issue by creating a pair of companion books. The authors have worked with The Infrastructure Security Partnership (TISP), a subcommittee of the Society of American Military Engineers (SAME), to disseminate this collective knowledge via a free download on their website. The book descriptions and corresponding links are as follows:

“Resilience: Managing the Risk of Natural Disaster” considers risk management strategies, risk identification methods, and pre- and post- event activities to minimize risk. Post-event recovery is a more widely understood field, as practitioners have a plethora of lessons learned from completed projects. Pre-event planning as a means of preventing damage and downtime is a lesser developed field, and this book organizes both literature supported data and the authors’ anecdotal experiences into a framework for disaster management, spanning pre- and post- event.

“Resilience: An Engineering & Construction Perspective” introduces the reader to many concepts but we will draw attention to three in particular. First, the importance of identifying, assessing and tracking resilience. Second, how post-disaster construction occurs in a changed project deliver framework. Finally, the commonalities between resilience and business continuity.

The following excerpts and graphics are from the first of the two books referenced above “Resilience: Managing the Risk of Natural Disaster” and the conclusions presented herein, should be considered narrowly focused when compared to the scope of the book.

“Resilience” has recently become a cure-all buzzword. Its varied concepts have been applied across developed and developing nations, with fields ranging from ecology, psychology, and sociology to community planning, engineering, economics, supply chain management, infrastructure, and corporate management. It seems to be a panacea, but when searching for the definition of resilience, the results are inconsistent. This book will not offer an all-encompassing definition of resilience, but instead will give practical insight into community, corporate, and governmental resilience.

The Community and Regional Resilience Institute (CARRI) dissected resilience into attributes and applications, ultimately defining the term in their 2013 paper “Definitions of Resilience: An Analysis.”[1] The report states that a definition of resilience should embody the following core concepts:

- Resilience is an inherent and dynamic attribute of the community.

- Adaptability is at the core of this attribute.

- Any adaptation must improve the community; it must result in a positive outcome for the community relative to its state after experiencing adversity.

- Resilience should be defined in a manner that enables useful predictions to be made about a community’s ability to recover from adversity.

Based on these principles, CARRI derived the following definition, which is foundational to this book:

“Community resilience is the capability to anticipate risk, limit impact, and bounce back through survival, evolution, and growth in the face of turbulent change.”

The intent of this work is not to offer the perfect solution to resilience. Instead, the hope is that the book will push forward the conversation on resilience. The book does not offer exhaustive definitions and reviews. Instead, the goal is to give a brief overview of salient topics and reveal the connections between them.[2]

Introduction

Over the last several decades, the world has experienced an increase in frequency and magnitude of natural and man-made hazards, and this trend is anticipated to continue for the foreseeable future. Human migration patterns over the past century have also exacerbated the effects of natural hazards, leaving all stakeholders more at risk than ever.

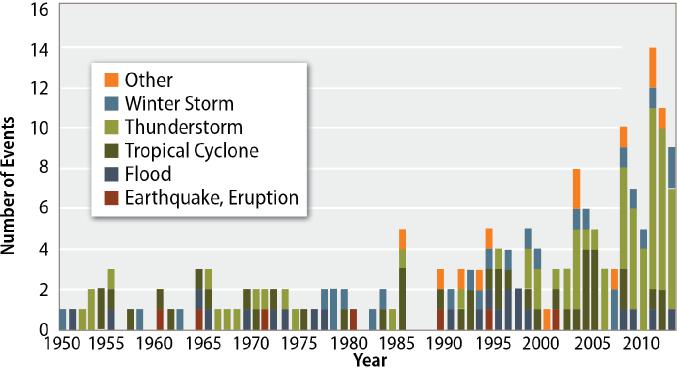

Increasing Magnitude, Frequency, and Cost of Disaster. Over the past few decades, data indicates that there are more natural hazard events and that there are higher economic impacts from these events. Research suggests that the increase in frequency and magnitude of weather-related events is tied to climate change (whether it be a natural cycle or human caused). In Building Safer Cities, Torben Juul Andersen notes that in the past 30 years, the frequency of disaster events has quadrupled, economic losses have increased by a factor of 2,000 to 3,000, and insurance losses have increased by a factor of 1,000.[3] The economic losses have far outweighed economic growth figures for the same period, suggesting that factors beyond the increase in number of events have impacted loss figures. These loss trends can be seen in Figure 1.

Additionally, in Catastrophe Modeling: A New Approach to Managing Risk, the author Grossi notes that losses from individual disasters during the past 15 years (as of 2005) are an order of magnitude above what they were over the previous 35 years. Figure 1 shows an increase in the annual number of high-loss catastrophes in the United States (defined as $1 billion in economic loss and/or 50 fatalities).[4] Further emphasized throughout this book, Grossi states, “Residential and commercial development along coastlines and areas with high seismic hazard indicate that the potential for large insured losses in the future is substantial. The increasing trend for catastrophe losses over the last two decades provides compelling evidence for the need to manage risks both on a national, as well as on a global scale.”[5]

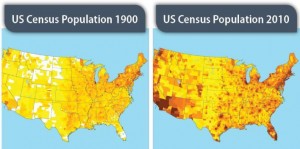

Who is at Risk? – The U.S. population has increased in most areas, but the largest increases are in coastal areas, indicating a population shift towards the coast over the last century. In 2010, 39% of the U.S. population lived in coastal shoreline counties, which represent less than 10% of the U.S. land area.[6] Figure 2 compares the population by county in 1900 and 2010. The shift towards the coastline is expected to continue, with the population density in coastal areas expected to increase at more than three times the national average between 2010 and 2020.[7]

As population increases, urbanization creates other concerns. Infrastructure, which has largely been neglected in the United States, has deteriorated, and population growth has overloaded the systems, often leaving them functionally obsolete. Poor urban planning has increased the risk for flooding and landslides. As noted in the State of the Environment and Policy Retrospective, seismic activity has remained constant over recent years, but the effects of earthquakes on the urban population appears to be increasing.[8] Because individuals provide the necessary labor for industry, the private sector (industry) has similar migration patterns to the population as a whole, which means it is at similar risk.

Community Context

The citizens and industry mentioned previously are part of an ecosystem – their community. For purposes of discussion in this book, the community is divided into the following four sectors: public sector, private sector, citizens, and the insurance industry (Figure 3). The insurance industry fits within the private sector, but since it also serves as a risk management opportunity, this book will address it separately. The following text details the interconnectedness of the sectors by analyzing how they acquire funds required to operate.

- Public sector. Operating funds are generated through various forms of taxation of the private sector, citizens, the insurance industry, and public employees.

- Private sector. Operating funds are generated by selling services and goods to the public sector, citizens, private sector, and insurance industry.

- Citizens. Operating funds are generated by performing services for the public sector, private sector, insurance industry, and other citizens.

- Insurance. Operating funds are generated by investing available capital and charging fees for taking on risk from the private sector, citizens, the public sector, and in some cases, other insurers.

Each of these sectors is reliant on the others, which creates challenges. Infrastructure, for instance, impacts both government and private industry, which makes financing mitigation difficult. Additionally, government recovery programs primarily focus on individual and public assistance but largely overlook the private sector (with the exception of some small business loans). When any of the four sectors falter, all suffer as a consequence. Nearly 7,900 businesses were permanently shut down in southeast Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina,[9] and similar cases have emerged from Superstorm Sandy. These shutdown businesses reduce tax revenue to government, reduce available jobs to citizens, reduce the business-to-business customer base for other businesses, and reduce potential clients for insurers. With private industry serving as the primary source of income for the public sector (taxation), citizens (income), and insurance (premiums), it is imperative to develop approaches that will allow for rapid recovery of the private sector.

Recommendations

As discussed throughout the book, we live in an interconnected society. We are only as strong as our weakest links. We must seek to build resilience as a community, working in lockstep with one another. The following suggestions are intended to help us more effectively do so:

- Align Cost and Risk. We need to better align insurance premiums with risk. Government regulation and other factors often drive premiums, which may not accurately represent risk. Additionally, as a society, we should be cautious with providing programs that potentially incentivize risky behavior.

- Build a Resilience Code. The implementation of building codes and the advancement of emergency management programs (including disaster preparedness and evacuation) have worked very well to reduce the loss of life from hazard events. As evidenced in numerous studies, the number of disasters reported and the number of people affected has increased drastically, but the loss of life has decreased significantly. Building codes were designed to save lives, and they have done that well. The next step is to create a “resilience code,” designed to minimize impacts to property and business interruption.

- Develop Common Understanding. In order to communicate across the four sectors discussed in this book, we must all work from a common understanding. This understanding includes both terminology and evaluation of risk. We must develop a standard vernacular that bridges sectors. We must also create a common language for risk. The concept of a credit score was developed to standardize risk to lenders so individuals could be compared against one another. A “resilience score” should be developed so hazard risk profiles can be compared against individuals, companies, infrastructure, or communities.

Once we have a common language, a means of measuring risk and resilience, then we can financially reward those who have taken appropriate actions. There needs to be a return on investment for making the right decisions, whether that means placing facilities in less vulnerable locations, investing in resilient design or investing in robust pre-event planning. Resilience is not a destination but rather a journey that we must all embark upon as a team.

Closing

We hope you find these books of interest and value and recognize that these considerations apply to both public and private infrastructure and facilities and that resilience and business continuity considerations have common frameworks.

[1] Definitions of Community Resilience, (Washington, D.C.; Community and Regional Resilience Institute (CARRI), 2013), available at http://www.resilientus.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/definitions-of-community-resilience.pdf.

[2] David Vaughn, Jeff Plumblee, Jonathan Vaughn, and Bob Prieto, Resilience: Managing the Risk of Natural Disaster, (2015), available at http://www.same.org/images/stories/Councils/TISP/Resilience_ManagingRisk.pdf.

[3] Alcira Kreimer, Margaret Arnold, and Anne Carlin, eds., Building Safer Cities: The Future of Disaster Risk, (Washington, D.C.: The World Bank, 2003), available at http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2003/12/05/000012009_20031205154931/Rendered/PDF/272110PAPER0Building0safer0cities.pdf.

[4] “2013 Natural Catastrophe Year in Review,” Munich RE, Jan. 7, 2014, http://www.munichre.com/us/property-casualty/events/webinar/2014-01-natcatreview/index.html.

[5] Patricia Grossi, and Howard Kunreuther, eds., Catastrophe Modeling: A New Approach to Managing Risk, (New York: Springer, 2005).

[6] “The U.S. Population Living at the Coast,” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, last modified March 14, 2013, http://stateofthecoast.noaa.gov/population/welcome.html.

[7]Ibid.

[8] United Nations Environment Programme, “State of the Environment and Policy Retrospective: 1972-2002,” in GEO-3: Global Environment Outlook (London: Earthscan Publications Ltd., 2002): 272-273, available at http://www.grida.no/geo/geo3/english/pdfs/chapter2-9_disasters.pdf.

[9] Kathy Chu, “Small Businesses Struggle to Recover from Katrina,” USA Today, Aug. 29, 2007, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/smallbusiness/2007-08-28-katrina-finances_n.htm.