The concept of “Smart Cities” is increasingly dominating the conversation around the future of urban environments. As more and more cities rush to embrace this concept, Smart City projects are rapidly outpacing the policies governing their development. While Smart City projects present incredible opportunities for municipalities to modernize their operations and improve efficiency and cost-effectiveness, these projects also introduce a range of security challenges. Incorporating holistic risk management principles into Smart City planning efforts will promote long-term resilience of Smart Cities.

What is a Smart City?

The general goal of a Smart City is to collect immediate data on everything from traffic patterns to home water use to emergency services deployments, to analyze that data, and to use that information to make the city work more efficiently for everyone. In general, Smart Cities incorporate at least five of the following parameters:

- Smart Governance and Education

- Smart Healthcare

- Smart Buildings

- Smart Mobility

- Smart Infrastructure

- Smart Technology

- Smart Energy

- Smart Citizens[1]

Using this integrated information, a Smart City can improve the resilience of the power grid, prioritize road maintenance projects to match traffic needs, or make it easier to predict how crowds might react in an explosion or how disease might spread. Overall, Smart City projects can produce a range of reliability, predictability, and efficiency benefits.

However, a fundamental challenge exists when evaluating Smart City projects and planning for their impact: there is no singular, set definition of a Smart City. For some, a Smart City is defined by its use of technology, such as the Internet of Things (IoT) and the need to optimize operations.[2] Other cities focus on a process-driven approach that evaluates how the city engages with Smart City projects and users to make cities more resilient and efficient.[3] Other Smart City projects focus on a citizen/consumer framework, in which a Smart City is predicated on residents and visitors using the internet and data to make more informed choices about lifestyle, work, and travel options.

Ultimately, Smart Cities are not about installing new gadgets or technology, or even about new data collection. Smart Cities are about changing how cities operate and improving their ability to build new connections between technology, data, citizens, planners, and government.

Smart City Growth

Regardless of how a Smart City is defined, the number of cities that consider themselves “smart’ is growing, mirroring the rapid growth of urban populations. The year 2008 marked the first year in history in which at least 50 percent of people worldwide lived in cities.[4] As the number of people moving to cities grows, cities are looking to scale services, reduce costs, and seek efficiencies. Smart City technologies are a way to realize these goals.

IoT devices are leading this technology revolution as Smart Cities are increasingly installing IoT devices to support Smart Cities projects. Approximately 1.6 billion devices were used in Smart Cities in 2016, and it is projected that figure will rise 40 percent in 2017 to 2.3 billion.[5] Some estimates claim that by 2020, there will be more than 30 billion IoT devices in use worldwide.[6]

Smart City initiatives are attracting significant public investment. City governments will invest $41 trillion over the next 20 years to upgrade infrastructure to benefit from the IoT.[7] Further, funding is not limited to municipal spending. The Department of Transportation has advanced $165 million in Smart City solutions to ease congestion and improve driver and pedestrian safety.[8] The National Science Foundation has devoted $60 million for FY16 and planned investments in FY17 for Smart City projects.[9] Those grants include funding to establish partnerships between the City of Chicago, the University of Chicago, and Argonne National Laboratory for smart sensor installation throughout the city to track air quality, noise, and traffic conditions.[10] Other projects include $8 million in grant funding for local governments to study dynamic bus tracking and ride sharing efforts and the impact on road conditions.[11]

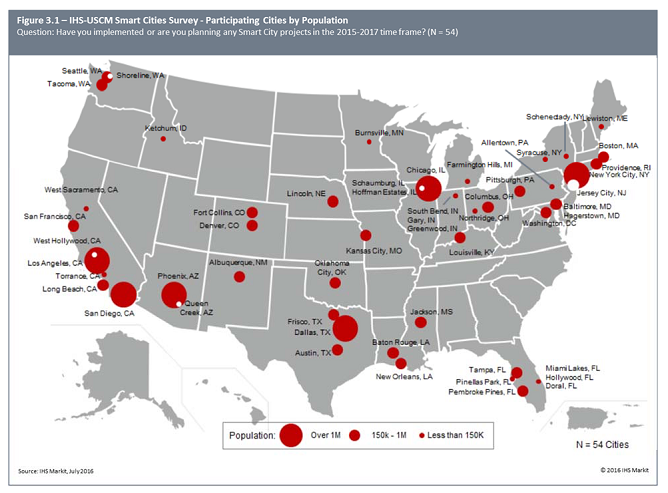

Those investments are not limited to any particular geographic region: cities of all sizes are investing in Smart Cities technologies. As shown in the graphic below, geographic and population dispersion of investments in Smart Cities is varied.[12]

Smart Cities Face a Broad Array of Challenges

While this growth in technology presents tremendous opportunities, there are also challenges. Technology, innovation, and investment is far outpacing risk management planning and governance across various spectrums.

Political challenges can materialize due to uneven or lack of access to Smart City data and analysis, and in privacy and civil rights concerns.

Economic challenges can transpire given increased replacement and repair costs with new technologies. Indeed, it may be an extreme cost for an uncertain payoff, or without an understanding of a potential return on investment.

Technical challenges can present given the lack of security in IoT devices and the fact that interconnectivity and interdependencies dramatically increase vulnerabilities—Smart Cities have already experienced malicious attacks, unintentional collapses of critical infrastructure, and systemic failures that have cascaded across networks. In addition, new technologies can generate their own risks—for example, system failures can occur due to unexpected security flaws caused by connecting smart networks to older, insecure devices.

Operationally, Smart Cities are falling victim to the same “headlong rush” challenge that has often plagued rapid infrastructure growth—in the race to start new projects and incorporate advanced technologies, planners may not take time to understand and incorporate lessons learned from previous iterations. There is a lack of quality control. Projects are prioritized based on availability and a desire to launch new efforts rather than as part of long-term planning to meet projected growth and needs. Smart Cities rely on optimizing operational efficiencies throughout networks and services, which makes it difficult to introduce security measures that may appear to slow process flows or raise costs.

Public officials often struggle with managing smart investment decisions involving security and resilience. So how do we help them? A smart idea is to incorporate risk management in the early phases of design and development for Smart Cities projects. In particular, leveraging existing Federal resources can support these efforts and help advance a “holistic” approach to security and resilience in Smart Cities.

Incorporating Risk Management into Smart Cities Planning

The “headlong rush” challenge discussed earlier and the focus on near-term security measures creates an environment that is not conducive to thinking about what it will take to ensure a more resilient Smart City. Moreover, it creates an environment that fixates on new projects and developments, overlooking the essential role that maintenance and upkeep play in long-term infrastructure security and resilience.

While a focus on near-term security measures, such as patching networks, is essential, it must be done concurrently with an eye to the future. Resilience requires longer-term thinking—the type of thinking that is linked to effective use of risk management principles. The increase in Smart Cities projects presents an opportunity to incorporate risk management principles that result in more resilient cities.

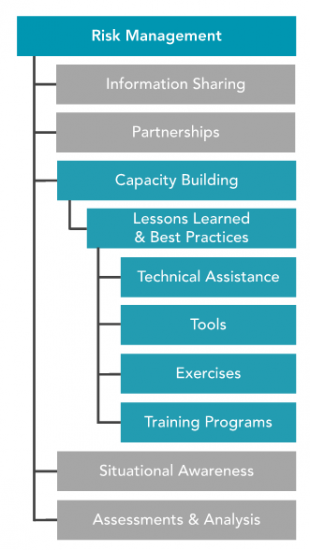

Holistic risk management can be a lever for building resilience in Smart Cities projects—specifically through assessments and analysis, partnerships, information sharing, capacity building, and situational awareness. For example, through cross-domain, cross-sector assessments and analysis we can move away from a focus on individual assets to a systems-based approach. Through cross-domain, cross-sector information sharing and capacity building, we can begin to merge data collection. Strong partnerships developed prior to incidents, and ample situational awareness during incidents, will ensure more cross-network, cross-jurisdiction coordination of cascading incidents.

Incorporating risk management at the outset improves the ability of Smart Cities to ensure long-term resilience, both in developing new projects and maintaining and operating existing components. Resilience planning builds the partnerships and information sharing frameworks needed to prepare for new challenges in the dynamic world of Smart Cities. It helps support the analysis and assessments needed to have a comprehensive situational awareness of new capabilities, the interconnections between them, and the emerging risks that Smart Cities face. And it makes it possible to build resilience capacity throughout the Smart City and its systems.

Federal Resources Can Increase Resilience in Smart Cities

Federal resources will play a key role in increasing resilience in Smart Cities, as translating risk management principles into Smart Cities planning and can be used to promote a more holistic approach to resilience planning.

Federal resources can be a mechanism for bridging the cyber and physical domains, as well as ensuring planners, engineers, urban designers, operators, governments, and responders work together in the design phase. Specifically, they can communicate how the resources function, their relationships, their limitations, and how they can be used to determine priorities. These resources, if applied on a systems level, can provide broader understanding of the costs and benefits of certain types of investments, tradeoffs, especially in the planning stages.

However, these resources are often not linked to the needs or capabilities of Smart Cities planners. Too often, they are products created in a vacuum, rather than being tailored to meet the day-to-day needs of stakeholders.

Recommendations

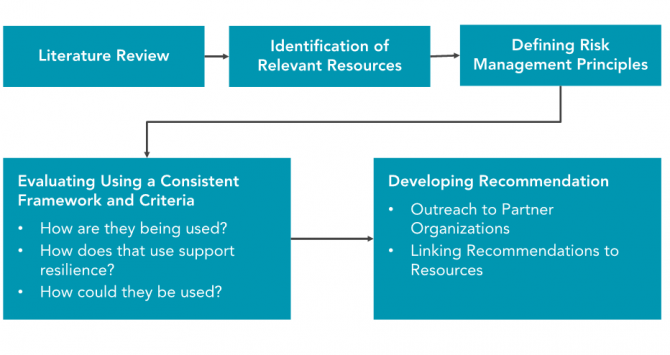

First, a literature review and identification of existing Federal resources applicable to Smart Cities is needed.

Next, determining cross-cutting risk management principles used in these tools will help ensure Smart Cities are coalescing around a shared set of objectives.

Further evaluation of these resources and feedback from stakeholders on how they are being used will help drive the incorporation of these risk management principles into Smart Cities planning efforts.

Finally, to encourage community use of these risk management principles and resources, we must encourage buy-in from stakeholders at all levels. Governance bodies have different ideas of what will make their Smart City successful, but we need to ensure they share resilience and risk management objectives. To do so, we must drive improved communications around challenges, encourage sharing pathways, and enhance awareness and understanding of common risks and possible mitigation strategies, which will ultimately result in smarter, more resilient cities.

References

[1] Ivan Fernandez, “Global Smart Cities Market to Reach US $1.56 Trillion by 2020,” Connectivity and the Emergence of Smart Cities and GIL (Australia: Frost & Sullivan., 2014), https://ww2.frost.com/news/press-releases/frost-sullivan-global-smart-cities-market-reach-us156-trillion-2020.

[2] Michael Kehoe et al., Smarter Cities Series: A Foundation for Understanding IBM Smarter Cities, (IBM, 2011), https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/55e0/c011168f3993f79cdf367980be56b5edb5b7.pdf.

[3] Smart Cities: Background Paper, United Kingdom Department for Business Innovation & Skills, Oct. 2013, UK National Archives BIS/13//1209, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/246019/bis-13-1209-smart-cities-background-paper-digital.pdf.

[4] United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2008 Revision, Highlights, Working Paper No. ESA/P/WP.210 (New York: United Nations, 2009), http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2008/wpp2008_highlights.pdf.

[5] “Gartner Says Smart Cities Will Use 1.6 Billion Connected Things in 2016,” Gartner, Dec. 7, 2015, http://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/3175418.

[6] Sam Lucero, “IoT Platforms: Enabling the Internet of Things,” IHS Technology Whitepaper, March 2016, https://cdn.ihs.com/www/pdf/enabling-IOT.pdf.

[7] Aneri Pattani, “Building the City of the Future – at a $41 Trillion Price Tag” CNBC, Oct. 25, 2016, http://www.cnbc.com/2016/10/25/spending-on-smart-cities-around-the-world-could-reach-41-trillion.html.

[8]“Secretary Foxx Participates in White House Frontiers Conference, Announces Nearly $65 Million in Advanced Technology Transportation Grants,” U.S. Department of Transportation Press Office, Oct. 13, 2016, https://www.transportation.gov/Briefing-Room/Advanced-Technology-Transportation-Projects.

[9]“NSF Commits More than $60 Million to Smart Cities Initiative,” U.S. National Science Foundation, Sept. 26, 2016, https://www.nsf.gov/news/news_summ.jsp?cntn_id=189882.

[10] Robert Mitchum, “Chicago Becomes First City to Launch Array of Things.” University of Chicago News, Aug. 29, 2016, https://news.uchicago.edu/article/2016/08/29/chicago-becomes-first-city-launch-array-things.

[11] “The US is Investing $165 Million Into Smart City Solutions,” Business Insider, Oct. 15, 2016, http://www.businessinsider.com/the-us-is-investing-165-million-into-smart-city-solutions-2016-10.

[12] “Cities of the 21st Century: 2016 Smart Cities Survey,” The United States Conference of Mayors, Jan. 2017, https://www.usmayors.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2016SmartCitiesSurvey.pdf.